The Interplay of Perception, Space, and Meaning: Exploring the Cognitive and Metaphysical Dimensions of Visual Artefact’s

- Jan 7, 2025

- 8 min read

1. Visual Artifacts as Metaphysical Catalysts

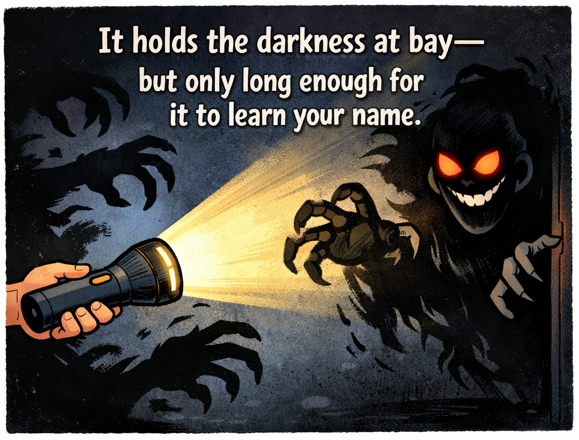

The clip unveils more than a mere depiction of a physical landscape; it acts as a profound visual metaphor, bridging the tangible and the intangible. At its core, it suggests a dynamic interplay between opposing forces: order and disorder, permanence and impermanence, control and entropy. Each element within the scene invites deeper reflection, moving beyond surface aesthetics into the realm of existential and metaphysical inquiry.

Take, for instance, the weathered path marked by cracks and imperfections. This is more than a simple visual of wear and tear; it becomes a poignant symbol of time’s inexorable passage and its capacity to erode even the most solid constructs. The cracks might evoke notions of the Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi, which finds beauty in imperfection, impermanence, and the incomplete. At the same time, the path’s very existence signifies human intent—an effort to create permanence within a landscape that resists it. Does the human impulse to shape, pave, and design reflect a rebellion against the natural cycles of decay, or does it merely highlight humanity’s futile attempt to defy entropy? The path itself, caught between function and symbolism, stands as a bridge between these questions.

The adjacent flora offers a counterpoint to the path. While carefully curated to create an aesthetic balance, the vegetation remains subject to the forces of decay and ecological unpredictability. Here, nature’s resilience and fragility coexist, revealing the duality inherent to its relationship with humanity. The act of cultivation—pruning, planting, ordering—represents the desire to impose human will upon nature, to make the untamed orderly. However, this is a precarious dance, as nature is both ally and adversary in this pursuit. The presence of the flora invites an unsettling question: Does humanity’s effort to cultivate nature reflect mastery, or does it reveal an underlying fear of chaos?

These dualities—order and disorder, permanence and impermanence—create a visual and conceptual tension, prompting an investigation into the limitations of sensory perception. How much of this landscape is “real” versus how much is a subjective construct shaped by the observer’s biases, cultural context, and sensory filters? The weathered path and curated vegetation may seem mundane, but their layered symbolism transcends physicality.

Philosophically, this interplay recalls ideas from thinkers like Immanuel Kant, who argued that sensory perception is inherently limited, filtered through human categories of understanding. Similarly, modern theories in phenomenology suggest that what we perceive as “reality” is always incomplete—a partial rendering influenced by our own subjectivity. This invites a provocative discourse: Can any single observer capture a truly holistic reality, or are all perceptions fragmented and filtered? And, if perception itself is flawed, does the act of interpreting visual artefacts become a creative endeavour rather than a pursuit of objective truth?

The clip’s broader message lies in its ability to be both evocative and interrogative. Its juxtaposition of opposing forces compels the observer to confront the paradox of being—to seek meaning within the cracks, the cultivated yet transient flora, and the human compulsion to impose order on a world that resists it. These tensions, rather than offering answers, pose questions that resonate across disciplines: science, philosophy, and art.

The metaphorical landscape thus becomes a metaphysical catalyst, challenging us to consider not only how we see but also what we seek when observing. Are we striving to impose meaning where there is none, or are we uncovering layers of truth embedded within chaos? Such questions remain open to interpretation, leaving space for discourse, debate, and the inherent subjectivity of human thought.

2. Cognition and the Perception of Space

Cognitive science reveals that perception is not a passive reception of external stimuli but an active, dynamic process shaped by the brain’s internal frameworks. As theorised by Clark (2013) and others, perception operates through a predictive model, wherein sensory inputs are constantly interpreted and reconstructed based on prior experiences, expectations, and cultural conditioning. In this sense, what we see is as much a product of our minds as it is of the physical environment. The clip in question serves as a striking demonstration of this interplay, blurring the boundary between external reality and internal meaning-making.

Consider the cracks in the pavement. To one observer, these might symbolise decay, evoking a sense of entropy or the inevitable passage of time. Another observer might interpret them as veins or conduits, channels through which life metaphorically flows. Such attributions, while meaningful to the observer, are not intrinsic to the cracks themselves; they arise from the cognitive act of “filling in the gaps.” This phenomenon aligns with Gestalt psychology, which posits that the human mind seeks patterns and wholes, even where none explicitly exist. Are the cracks merely imperfections in a constructed surface, or are they something more profound, imbued with the narratives we project onto them?

Similarly, the placement of flowers in the scene engages the observer’s cultural and personal schemas. In many traditions, flowers carry symbolic weight, representing life, beauty, or impermanence. A Western observer might interpret the flowers as ornamental or decorative, while an Eastern perspective influenced by Zen aesthetics might emphasise their transient, fleeting nature. Here, the perception of space becomes an act of translation: external stimuli are filtered through the lens of cultural conditioning, and meaning is attributed accordingly. The flowers, like the cracks, are thus transformed from neutral elements into carriers of subjective significance. But this process raises questions: To what extent is perception “real”? Can the essence of a space ever be divorced from the observer’s interpretative frameworks?

From a neuroscientific standpoint, this dynamic can be linked to the brain’s reliance on predictive coding. According to Clark (2013) and Friston’s free-energy principle, the brain constantly generates hypotheses about the external world and updates these models based on sensory feedback. When encountering a scene, the observer is not merely recording visual details but actively constructing a mental representation, guided by prior knowledge and expectations. This process, while efficient, is also inherently biased. It suggests that no two individuals perceive the same space in identical ways, as their cognitive frameworks and cultural contexts differ.

Philosophically, this interplay between perception and cognition aligns with the ideas of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, who argued that perception is an embodied experience, deeply rooted in the observer’s lived reality. The cracks, flowers, and spatial arrangements within the photograph are not fixed “things” but phenomena that emerge through interaction with the observer. This perspective challenges objectivist notions of reality, emphasising instead the co-creation of meaning between the environment and the perceiver. How, then, do we reconcile the subjective nature of perception with the desire to understand space objectively? Is it possible to disentangle the cognitive and cultural filters from the “raw” experience of a scene?

Ultimately, the perception of space is as much about the observer as it is about the observed. The cracks and flowers serve as cognitive anchors, grounding the mind’s interpretative processes while simultaneously revealing the inherent subjectivity of these interpretations. Such an understanding opens the door to broader discourse: Does perception ever reveal an “objective” reality, or is it forever entwined with the biases, histories, and expectations of the perceiver? In examining these questions, we not only probe the mechanisms of cognition but also reflect on the ways in which we construct our realities.

3. Metaphysics in Everyday Contexts

The artefact presented above demonstrates how environments can evoke profound metaphysical questions. What is the significance of a crack in a pavement? Is it merely a sign of wear, or does it symbolise broader themes of entropy and renewal? This ambiguity illustrates how perception operates on both sensory and metaphysical levels, revealing hidden dimensions within the ordinary.

Conclusion

This exploration of perception underscores its dual role as a sensory and metaphysical phenomenon. The artifacts within this article serve as entry points into a larger dialogue about how individuals interpret their environments. By bridging Aristotelian metaphysics, modern cognitive science, and phenomenological inquiry, this article demonstrates how seemingly ordinary artifacts can provoke extraordinary questions. Ultimately, perception is revealed as both a tool for navigating the physical world and a gateway to abstract understanding, urging us to reconsider the boundaries of human experience.

References and Summaries

For 1. Visual Artefacts as Metaphysical Catalysts

1. Kant, Immanuel. Critique of Pure Reason. Translated by Paul Guyer and Allen W. Wood, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

• This seminal work explores the limitations of human perception and cognition. Kant argues that sensory perception is filtered through innate categories of understanding, emphasising that humans cannot access the world as it is (noumenon) but only as it appears to them (phenomenon). The discussion on the limitations of sensory perception in interpreting reality is deeply rooted in Kantian philosophy.

2. Saito, Yuriko. Everyday Aesthetics. Oxford University Press, 2007.

• Saito’s work examines how aesthetics permeates daily life, particularly through ordinary objects and environments. The book argues that seemingly mundane elements, such as cracks or flora, carry deep aesthetic and philosophical meanings depending on their context and interpretation.

3. Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Phenomenology of Perception. Translated by Donald A. Landes, Routledge, 2012.

• This book presents perception as an embodied, subjective experience. Merleau-Ponty contends that meaning emerges through interaction between the perceiver and the world, challenging the notion of an objective reality. The emphasis on perception as a co-creative process aligns with the analysis of the interplay between order and disorder.

4. Koren, Leonard. Wabi-Sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers. Stone Bridge Press, 2008.

• Koren introduces the Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi, which celebrates imperfection, impermanence, and the incomplete. The concept is invoked in the discussion of the cracks in the path and the transient nature of the flora, offering an aesthetic framework for interpreting the scene.

5. Ball, Philip. Critical Mass: How One Thing Leads to Another. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2004.

• This book explores the interplay between order and chaos in physical, social, and natural systems. Its insights are used to frame the discussion of dualities in the scene, highlighting how chaos and order coexist as natural counterparts.

For 2. Cognition and the Perception of Space

1. Clark, Andy. Mindware: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Cognitive Science. Oxford University Press, 2013.

• Clark introduces cognitive science theories, particularly predictive processing, which posits that perception is an active process shaped by prior knowledge and expectations. This forms the theoretical backbone for understanding how observers interpret space and assign meaning.

2. Friston, Karl. “The Free-Energy Principle: A Unified Brain Theory?” Nature Reviews Neuroscience, vol. 11, no. 2, 2010, pp. 127–138.

• Friston’s free-energy principle outlines how the brain minimises uncertainty by predicting sensory input and updating models based on feedback. This neuroscientific theory underpins the idea that perception arises from a constant interplay between prediction and sensory experience.

3. Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Phenomenology of Perception. Translated by Donald A. Landes, Routledge, 2012.

• As in the first response, Merleau-Ponty’s work is used to frame perception as an interactive process, where meaning arises from embodied experience rather than being inherent to objects themselves.

4. Koffka, Kurt. Principles of Gestalt Psychology. Harcourt, Brace & World, 1935.

• Gestalt psychology emphasizes the mind’s tendency to perceive patterns and wholes. This theory is central to understanding how cracks in pavement or floral arrangements are interpreted as meaningful by observers seeking coherence.

5. O’Regan, J. Kevin, and Noë, Alva. “A Sensorimotor Account of Vision and Visual Consciousness.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences, vol. 24, no. 5, 2001, pp. 939–973.

• This paper introduces a sensorimotor perspective on vision, arguing that perception arises through active engagement with the environment. It reinforces the idea that perception is not a passive process but one deeply shaped by interaction and cognition.

Summary of Use in Responses

• Kant and Clark: Explored the limitations of perception and its dependence on internal cognitive models.

• Merleau-Ponty: Provided a framework for understanding perception as an embodied and co-creative process.

• Koren and Saito: Highlighted aesthetic and philosophical interpretations of imperfection and order in everyday contexts.

• Friston and Gestalt Psychology: Offered insights into the brain’s predictive nature and tendency to perceive coherence.

• Ball: Connected concepts of order, chaos, and human interpretation within broader natural and philosophical contexts.

Comments